I like to photograph sunsets; many of my picture folders are populated with sunsets from different locations around the globe. Lately, I have been hitching rides on the International Space Station, where they get to see fifteen sunsets and sunrises every day. (I’ll explain later in this blog posting how I managed to take these photos without actually going through astronaut training.)

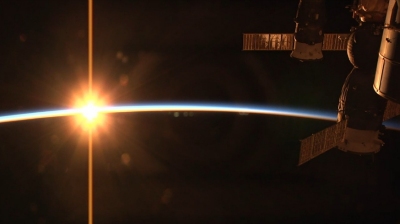

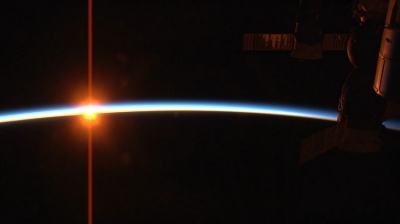

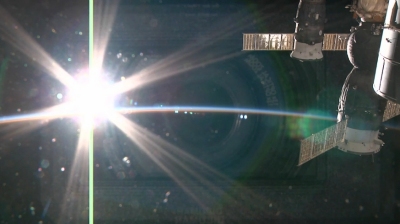

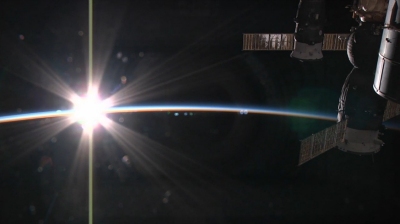

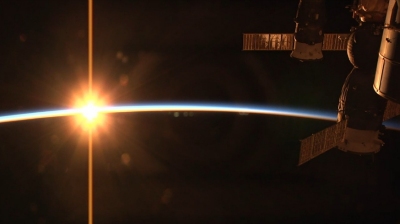

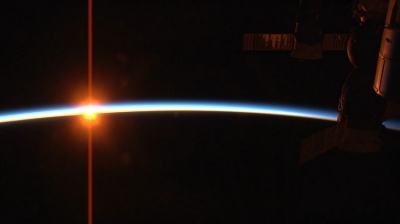

Here is a typical sunset sequence:

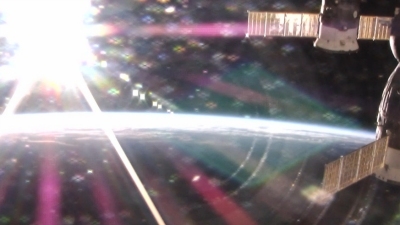

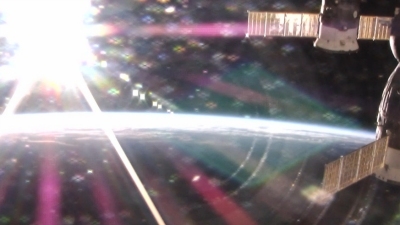

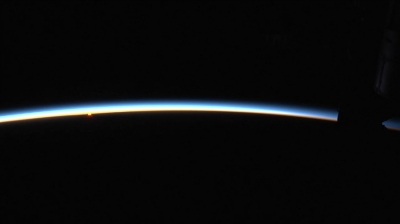

One would think that every sunset from space would look the same, but they are very different depending on the clouds at the horizon and the clarity of the air at that location and time. Sometimes, as the light of the sun goes through layers of atmosphere, it acts like a variable color filter. To illustrate, here is a sunset view with a wider angle. Notice the color of illumination on the ISS in the foreground. The light from the Sun starts out warm-ish white before touching the atmosphere. Then, it switches to blue-ish, then yellow-orange, then finally deep red before the light fades as the Sun slips behind the curve of the earth.

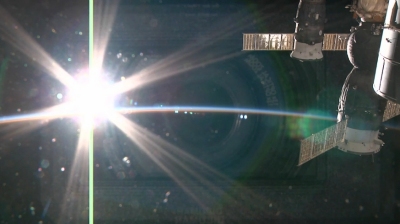

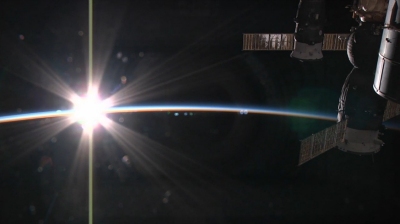

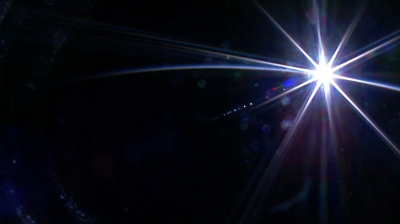

As many of you know, I also like sunrises. Here is one from space:

Sunrise can be particularly fun to watch, because you get to see the morning Sun glint off bodies of water big and small. For example, here the Sun reflects off the Pacific Ocean as we approach Africa from the southwest:

Shortly thereafter, the Sun reflects off Lake Ishiba Ng'andu in Zambia. In the foreground is Lake Bangweulu, right next to the smaller Lake Walilupe.

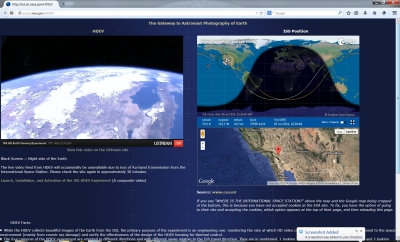

Earlier, I promised to tell you how I could shoot these pictures without actually leaving my house to perform astronaut training. In lieu of inviting actual visitors, the ISS-sponsoring nations have cooperated to provide a continuous HD live video feed: the

ISS HD Earth Viewing Experiment. There is one camera is pointing forward, two rear-facing, and one looking downward. The view switches between these cameras on a regular basis.

Here is a flight console showing the video feed, the ISS position, and a Google satellite image as we flew southeast toward Baja California. The Salton Sea is in the foreground:

I say "we flew" because that's what it feels like while watching the live video feed. In contrast to nature programs and documentaries, there are no talking heads, celebrity voiceovers, or cuts to an astronaut profile showing the small town where he/she grew up. It is just the silent realtime view out the window. I feel like I'm there, sans weightlessness.

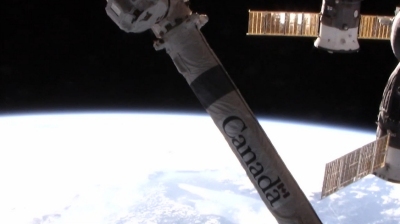

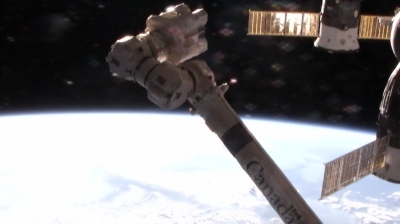

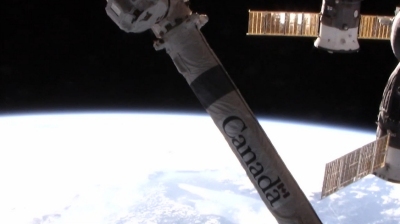

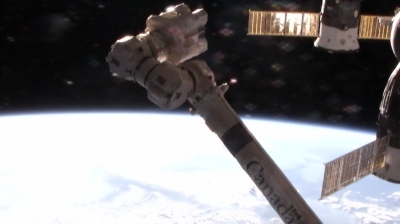

You never know what's going to show up outside your window. I was anticipating a sunset when out of nowhere, the Canadarm2 appeared (a.k.a. Space Station Remote Manipulator System, or SSRMS), smoothly and purposefully moving through the scene. (I guess the astronauts do have jobs to acccomplish, and are probably not gazing at the view like I am.)

The ISS orbit carries it over nearly every location on the globe at one time or another. Although many regions are obscured by clouds as we fly over, here are a couple of nice sunlit views that showed up outside my ISS window. The first one is the Nile Delta in Egypt. Although you can't see them at this distance, the cities of Cairo, Alexandria, and Port Said are on the edges of the Delta. The second shot shows the island of Cyprus, which is also visible near the top of the first photo.

The camera shutter button is the F10 key on my computer keyboard -- it activates a screen capture function which saves the current image as a PNG file. It's handy to have a dedicated function key to "take pictures" since you never know what interesting view will show up. For example, here is an opportunistic shot of the moon setting behind the earth. (Did I mention that I also like to shoot moonsets?)

So go ahead;

take your own ride on the ISS. While riding, your location will be shown

here. This may be a time-limited opportunity; the live video feed is currently an experiment; there is no guarantee it will continue indefinitely. But for now, it's a chance for us mere mortals to get glimpses of the world from space as the ISS circles the globe fifteen times per day.

Enjoy the trip!