On a recent trip to Jackson, Wyoming, we were treated to a very dark sky thanks to low light pollution and lack of moonlight. It's awe-inspiring to see so many more points of light than are visible from my backyard in a Portland, Oregon suburb. Of course, the brightest collection of stars we can see in a dark sky is the Milky Way, captured above with a series of 15-second photos at f/3.5 and ISO 6400. (Bonus: If you click on the image and zoom in a bit, you can see the Andromeda Galaxy in the upper-left.)

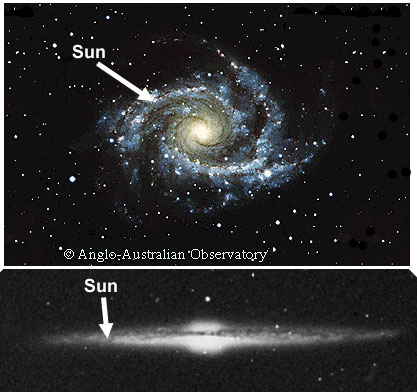

This view of the Milky Way stretches from horizon to horizon, and yet we still can't see the whole thing. To understand why, it helps to visualize of our position inside the Milky Way; we are "living on the edge" -- well, about 1/5 of the way from the edge of our disk-shaped galaxy.

(Image Source: http://stevekluge.com/geoscience/images/milkywaysun.jpg)

No matter where we look in the sky, the Milky Way is there. That famous archway in the sky glows brighter because the bulk of the galaxy's stars are toward its center. But essentially, every star we can see as a single point of light is still part of the Milky Way -- even if it's in the opposite direction from the galactic center.

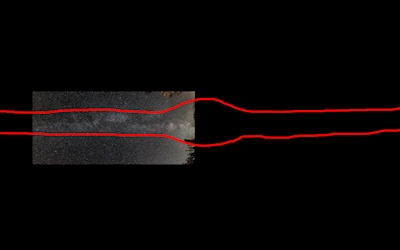

How could we arrange to see the whole thing, when it's all around us? You are already familiar with stitched panoramas. My Milky Way photo from Wyoming is a 17-shot stitched composite that crosses the whole sky. Let's tip it sideways and see how it fits into the galactic context:

As you can see, it's only big enough to show part of the Milky Way.

To see all of our galaxy, I would need to take my camera to dark-sky locations on earth representing both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, then combine all the photos -- about 300 of them -- to cover all portions of the earth's visible sky. And, to get a high-quality result, I'd need to stack 4 photos for each of the 300, for a total of 1,200 shots. The exposures would need to be about six minutes each, to gather enough light for a low-noise, high-resolution digital camera sensor. Last but not least, six minutes would ordinarily show star trails instead of stars. (The longest exposure you can do with a fixed camera at the necessary zoom level is about 15 seconds.) So, the camera would need to be placed on an equatorial mount with a clock drive to track the motion of the stars through the sky.

It would be a huge project, taking well over a year.

Fortunately, I don't need to embark on such an ambitious adventure; Serge Brunier has already accomplished the project. His result looks like this:

(Image source: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap090926.html)

Brunier's website includes a dynamic 360-degree view showing what it would look like if you were floating in space looking at the Milky Way. Using the keyboard arrow keys, you can look to the left, right, up, and down. In essence, Brunier packaged his amazing spherical composite in a 3D viewer. You can spin around and look behind, where it is clear that the Milky Way actually looks like a surrounding ring -- the stars between us and the galaxy's edge are still concentrated in a band, since they are part of the overall disk.

We are indeed living on the edge -- but still inside -- of the Milky Way.

I'll close this blog entry now, because once you go to Brunier's dynamic 360-degree view, you'll not want to come back. (Yes, it's that cool.)

1 comment:

As a small child I was treated to the Milky Way site like yours almost every nonrainy night. Yes in Western Nebraska that was our usual view. Now I seldom if ever get to see it! Well done!

Post a Comment